Asturians in West Virginia

By Luis Argeo

“We believed that they were going to the best place of the world, but they suffered a lot there. It was very hard for them. Very hard, yes”. Mrs. Covadonga Vega López speaks about her neighbours and relatives from Arnao, an Asturian coastal village that saw hundreds of metallurgical and mining workers shipping towards the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, far away, to the isolated mountains of West Virginia.

That was almost one century ago. They departed Spain seeking new opportunities, or as it is said in the movies, searching for the American Dream. The workers proceeding from the Arnao Royal Asturian Company of Mines ran up against a tepid welcome after landing at Ellis Island immigration offices in New York. They would eventually reach their own American Dream, although splashed with indifference, difficulties, and discrimination.

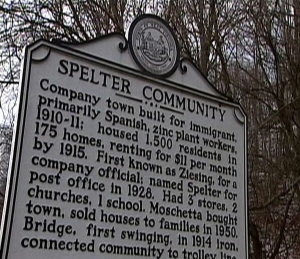

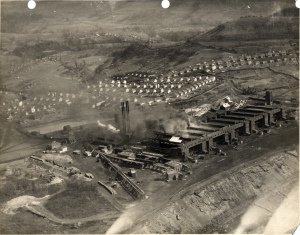

Their labor experience in mines, factories, and blast furnaces in their home country led them to those places where chimneys, shafts, and cooling towers proliferated among the woody green and the stony black of the coal valleys. They gathered in small company towns that were built for workers close to the factories — towns that belonged to the chemical and mining companies, with low-rent houses, storehouses, school, and church: towns like Spelter, Anmoore, and Moundsville in West Virginia, and Donora in Pennsylvania.

These were towns where Asturian immigrants were in the majority, places where for many years people could speak the Asturian language, ate fabada (mixture of beans and Spanish chorizo, bloody sausage), played the bagpipe, and danced the traditional Xiringüelu for fun. Asturian and United States histories converged in the hills, valleys, and rivers of the Appalachian region, thanks to the zinc workers.

“Wherever there were zinc factories, there were Asturians. They were those who better could stand such a na sty and helly work,” Isaac Suárez, octogenarian, son of Asturians, and born in Spelter, says in Spanish. “That’s why the Spanish language was very common in the smelting furnaces”.

sty and helly work,” Isaac Suárez, octogenarian, son of Asturians, and born in Spelter, says in Spanish. “That’s why the Spanish language was very common in the smelting furnaces”.

“The Asturians involved in the zinc industry thought of themselves as one community”, says Art Zoller Wagner, grandson of another Asturian who arrived in West Virginia in 1917. “They communicated with each other; traveled to each others’ fiestas, weddings, and funerals; and shared news about job opportunities. The experience of any of the locations would have had much in common with the others”.

Spelter, Harrison County, is today a dismantled and silent residential Clarksburg suburb. Nevertheless, its 175 wooden houses hosted 1,500 people of Asturian origin in 1915. All the families depended on the zinc mill that Grasselli Chemical Company had raised at the edge of the West Fork River. All of the families knew each other and, by and large, they were a happy community.

They used to organize espichas over the surrounding green meadows, which later on were called picnics. Any excuse was good to be in a good mood and celebrate a party full of Spanish sausages, p

ies, and potato omelettes. The bagpipe sounded daily, and they devised clever methods to draw liquor from berries and other forest fruits, even during those Dry Law years.

ies, and potato omelettes. The bagpipe sounded daily, and they devised clever methods to draw liquor from berries and other forest fruits, even during those Dry Law years.

Occasionally, they had to endure some intimidation from the Ku Klux Klan, or had to face the bosses and go on strike, but generally they made good use of the opportunity West Virginia gave them to succeed. They could even organize espicha parties to collect money to send to families that were suffering the devastation of the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) in Asturias.

Many of the immigrants came to West Virginia with the intention of earning their fortunes and returning to Asturias. They noticed, however, that the situation in Spain was not inviting enough for them to return. Besides that, they had to support those who remained in Asturias and other relatives who were arriving here with their empty  pockets. That was how the dream of the emigrant — one who hopes to return with the suitcase full of dollars — evaporated in these Harrison County communities. And then, their espichas, their bagpipes, and their traditional songs were slowly turning off to become more American, day after day.

pockets. That was how the dream of the emigrant — one who hopes to return with the suitcase full of dollars — evaporated in these Harrison County communities. And then, their espichas, their bagpipes, and their traditional songs were slowly turning off to become more American, day after day.

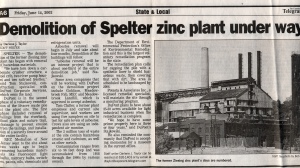

Today, Spelter does not even keep the skeleton of the factory up. It was dismantled in 2002. From the 1950’s, those Asturian families were dispersing all over the country, losing surnames, changing their customs, breaking the language walls. As the zinc mill languished, the old Asturian ways of life did, also. Nowadays, only a few descendants tend their Asturian roots. In the headstones of Spelter Cemetery, the names can be read: Joe Gutiérrez (1899-1952), Thomas Díaz (1886-1934), Frank Bango, and so on.

Jess Vázquez does not know what an Asturian beret is like and always wears a baseball cap, bearing the initials “WV.” Decades ago, Dolores Álvarez and her husband opened a Harley-Davidson motorcycle shop in Nutter Fort. Anita Menéndez is one of the few Asturian-Americans who has remained in Spelter. Born 74 years ago, she was one of the first female clerks of the Union National Bank to be promoted. She learned to speak Spanish with her grandmother and continues speaking it fluently and with old Asturian turns. “I’ll tell you something”, Anita says. “I’ve already traveled to Asturias three times, and the farms and the meadows remind me so much of these here [in West Virginia]. There in Spain, I am the American, and here I have always been the Spanish woman”.

Ron González is another of the few who continues living in Harrison County with nostalgia. He was employed for 46 years at the Spelter zinc factory, just like his father and grandfather, both from Asturias. He proudly shows any symbol, vest, flag, T-shirt, or pin related to the land of his forbears. Ron has a lot of free time since he retired, and when he is not in www.asturianus.org writing to his Asturian-American forum friends, he walks a couple of miles around the tourist paths that now occupy the missing railway trails that once connected the mines of the south with the state’s northern factories.

In Spain, Asturias is suffering a process of industrial restructuring as difficult and long as the one in West Virginia. Nowadays, it is one of the poorest, most forgotten provinces in Spain. Nature has been generous here, though, and hiking, mountain bikes, canoeing, rafting, and fishing are promoted activities throughout Asturias.

This autonomous region, situated on the Spanish north coast, has rugged sea cliffs and a mountainous interior as its key features. The rain, the leafy forests, the brown bears from the Cantabrian Mountains, and the cider are also distinctive. The people here recall their past as farmers, who often moonlighted at the mines and factories springing up around them. They find pride in their combative and struggled spirit from ancient Roman and Medieval times. Older people in Spain still remember how ferocious the oppression was after the Revolution of Asturias, the 1934 miners’ uprising that preceded the Spanish Civil War.

There are still several supporters of local traditions and customs, even in the main cities of Asturias. The preservation of regional folklore, ancient dialects, and rural traditions is not seen as the opposite of progress. Indeed, the safe and healthy way of life in Asturian towns and villages proves that the rediscovery of the old models still works in our times.

That was one of the things that surprised Ron González when he finally visited Asturias for the first time last September. He arrived from Spelter to discover his father’s and grandfather’s land with his own eyes. The most insignificant details become, sometimes, exotic surprises. That was Ron’s vision during his walks across Piedras Blancas, Castrillon County, the original place of his ancestors.

with his own eyes. The most insignificant details become, sometimes, exotic surprises. That was Ron’s vision during his walks across Piedras Blancas, Castrillon County, the original place of his ancestors.

“Oh, there is so much that is different in Asturias”, he says. “In Asturias, after work, the family goes to the town square, the kids play soccer, the ladies talk about whatever they talk about, the men talk about who knows what. I heard some of the men talking about what day last year that something happened, never did find out what happened, but they were into a heated argument over it. I went with my cousin to a sidewalk café. We sat down and drank a coffee with milk and just watched the people go by. All the ladies were dressed up in their finest dresses, the men were neat, as well as the kids. Everyone was enjoying life as it was meant to be enjoyed, talking to people you know, friends you meet on the street, and, yes, people you don’t know, like me. Then you go home as a family, eat as a family, spend the evening as a family.

“Here in West Virginia, you get home from work, but the kids are not at home. They are at a ball game. And your wife is cooking supper, and there is no town square to go to. There is no sidewalk café to sit at. Of course, there are bars you can go to, but you can’t take your wife there, like in Asturias. Here you eat supper, and then you sit and watch TV all evening till time to go to bed. In the U.S., if you don’t have a car, you can’t go anywhere. We are so spread out that we can’t walk”.

What Ron found exotic abroad may be what he hungers for at home. Besides the nostalgia, he also found a few symbols of his ancestors.

“I wanted to see the place where my grandparents came from, as well as my father. But I never found the home of my father’s family. No one knew where it was. It seems that the same thing is happening there that is happening here: as the old ones pass away, that part of history is gone with them. I think that is very sad”.

Both regions, the one in West Virginia and the one in Asturias, are searching for ways to preserve their past while looking ahead. No one should forget that the industrial heritage is also part of the culture. No one should let that part of the history pass away.

This article was originally published in Goldenseal Magazine (September 2009)

Old pictures courtesy Ron Gonzalez

***

Asturianos en Virginia Occidental (Traducción)

Por Luis Argeo

“Nosotros creíamos que se iban al mejor lugar del mundo, pero sufrieron mucho alla. Fue muy difícil para ellos. Muy difícil”. La Señora Covadonga Vega López habla acerca de sus vecinos y parientes de Arnao, una aldea costeña que vio zarpar a cientos de sus trabajadores mineros y metalúrgicos hacia el otro lado del Océano Atlántico, lejos de casa, hasta las solitarias montañas de Virginia Occidental.

Hace ya casi un siglo partieron de España en busca de nuevas oportunidades, o como dicen en las películas, en busca del sueño americano; pero los trabajadores provenientes de la Real Compañía de Minas Asturianas de Arnao, al llegar a las oficinas de inmigración de Ellis Island en el estado de Nueva York, se encontraron con un recibimiento más bien frío. Eventualmente estos españoles alcanzarían su propio sueño americano, no sin antes tropezar con un camino lleno de discriminación, dificultades e indiferencias.

Su experiencia laboral en las minas, fábricas, y hornos de su país natal los condujo a los verdes bosques y pedregosos valles de carbón, donde abundaban las chimeneas, pozos, y torres de refrigeración. Estos trabajadores se aglomeraban en las pequeñas aldeas pertenecientes a las compañías químicas y mineras, construidas para los trabajadores de la empresa, con viviendas a bajo costo, almacenes, escuelas e iglesias: aldeas como Spelter, Anmoore y Moundsville en Virginia Occidental y Donora en Pennsylvania.

Los habitantes de estos pueblos eran mayoritariamente inmigrantes asturianos, lugares donde por muchos años la gente podía hablar la lengua asturiana, comer fabada (una mezcla de habas y chorizo español), tocar la gaita, y bailar, por diversión, la danza tradicional: Xiringüelu. La historia de Asturias y Estados Unidos convergió en los montes, valles y ríos de la región de los Apalaches, gracias a los trabajadores de zinc.

“Donde quiera que haya fábricas de zinc, habrá Asturianos. Eran los únicos que podían soportar un trabajo tan pesado e infernal”, nos cuenta en español el octagenario Isaac Suárez, hijo de asturianos nacido en Spelter. “Es por ello que el castellano era tan común en los hornos de fundición”.

“Los asturianos que participaban en la industria del zinc se pensaban a sí mismos como una comunidad”, dice Art Zoller Wagner, nieto de otro asturiano que llego a Virginia Occidental en 1917. “Se comunicaban entre ellos; iban a sus fiestas, bodas, y funerales; e intercambiaban noticias de oportunidades laborales. La experiencia de una localidad tendrá mucho en común con las otras”.

Spelter, en el condado de Harrison, es hoy día un suburbio residencial de Claksburg deshabitado y silencioso. Sin embargo, sus 175 casas de madera acogieron a 1,500 personas de origen asturiano en 1915 donde todas las familias dependían de la fábrica de zinc, que la compañía química Grasselli había construido a orillas de río West Fork. Todas las familias se conocían entre ellas, y entre tanto, eran una comunidad alegre.

Solían organizarse espichas en los alrededores de las praderas verdes, que, después de un tiempo, fueron llamados picnics. Cualquier excusa era buena para estar de buen humor y celebrar una fiesta llena de chorizo, bizcochos, y tortilla de patata. La gaita sonaba a diario e incluso diseñaron un método astuto para sacar licor de bayas y otras frutas del bosque, aún en los años de la Ley Seca.

Ocasionalmente tenían que soportar algunas intimidaciones del Ku Klux Klan, o enfrentar a sus jefes e irse a huelga, pero generalmente aprovechaban las oportunidades que Virginia Occidental les brindaba. Incluso organizaban espichas para recolectar dinero y mandárselo a las familias que sufrían la devastación por la Guerra Civil Española en Asturias (1936-39).

Muchos de los inmigrantes llegaron a Virginia Occidental con la intención de ganar una fortuna y regresar a Asturias. Sin embargo, notaron que la situación en España no era la más conveniente para regresar. Aparte de eso, tenían que mantener a los que se habían quedado en Asturias y a otros parientes que llegaban con las bolsas vacías. Así fue como el sueño del emigrante- el de regresar a casa con la maleta llena de billetes- se evaporó en estas comunidades del condado de Harrison. Finalmente llegó el día en que las espichas, las gaitas, y las canciones tradicionales fueron cambiadas, lentamente, por música americana. Actualmente ni siquiera existe ya la estructura de la fábrica, la cual fue desmantelada en el 2002. Apartir de los años 50’s, estas familias asturianas comenzaron a dispersarse por todo Estados Unidos, perdiendo apellidos, cambiando sus costumbres y olvidando la lengua. Conforme la fábrica fue extinguiéndose, el antiguo modo de vida asturiano fue desapareciendo. Hoy en día, unos pocos descendientes preservan sus raíces asturianas. En una lápida en el cementerio de Spelter, se pueden leer nombres como: Joe Gutierrez (1899-1952), Thomas Díaz (1886-1934), Frank Bango, y así sucesivamente.

Jezz Vázquez no tiene idea de lo que es una boina asturiana, sin embargo, siempre porta una gorra de baseball con las iniciales “WV”. Hace algunas décadas, Dolores Alvarez y su esposo abrieron una tienda de motocicletas Harley-Davidson en Nutter Fort. Nacida hace 74 años, Anita Menéndez es una de las pocas asturiano-americanas que ha permanecido en Spelter. Fue una de las primeras mujeres de la Unión del Banco Nacional en ser promovida. Aprendió a hablar castellano con su abuela y continúa hablándolo fluidamente y utilizando viejos dichos asturianos. “Te dire algo”, dice Anita. “He viajado a Asturias tres veces y las granjas y los prados me recuerdan tanto a los de aquí [Virginia Occidental]. En España soy una americana, y aquí, siempre he sido la mujer española”.

Ron González es otro de los pocos que continúan viviendo nostalgicamente en el Condado de Harrison. Fue contratado durante 46 años en la fábrica de zinc de Spelter, como su padre y abuelo, ambos asturianos. Con orgullo muestra los símbolos relacionados con la tierra de sus ancestros: una bandera, un escudo, una playera, o un pin. Ron tiene demasiado tiempo libre desde que se retiró y cuando no está en el foro de www.asturianus.org, escribiéndole a sus amigos asturiano-americanos, camina unas cuantas millas alrededor del camino turístico, en lo que antes fueron las extintas vías del tren que alguna vez conectaron las minas del sur con las factorías del norte del estado.

En España, Asturias está sufriendo una reestructuración industrial tan complicada como la que hubo en Virginia Occidental. Hoy día es una de las provincias más pobres y olvidadas. Sin embargo, la naturaleza ha sido generosa en la región, y por lo tanto diversas actividades ecoturísticas, entre las que se encuentran el senderismo, el canotaje, el rafting y la pesca, han sido promovidas por todo Asturias.

Esta región autónoma, se encuentra situada en la costa norte de España y sus características físicas clave son las pendientes marítimas y sus interiores montañosos. Otros símbolos distintivos de esta región son la lluvia, los bosques frondosos, los osos pardos de las montañas cantábricas y la sidra. Los asturianos recuerdan su pasado como campesinos, aunque algunos, posteriormente, cambiaron la agricultura por irse a trabajar en las minas y en las fábricas que empezaban a brotar a su alrededor. Les causa orgullo su espíritu combativo y fuerte de la antigua Roma y la época medieval. La gente mayor en España aún recuerda cuán atroz fue la represión después de la Revolución Asturiana, el levantamiento minero de 1934 que precedió a la Guerra Civil Española.

Todavía existen varios defensores de las costumbres y tradiciones locales, aún en las principales ciudades Asturianas. La preservación del folklore regional, los dialectos antiguos, y creencias rurales no son vistas como retrocesos, al contrario. Sin duda, el saludable estilo de vida de los pueblos asturianos prueban que el antiguo modelo de vida sirve, aún, en nuestra época. Eso fue lo que más sorprendió a Ron González cuando finalmente visitó Asturias por primera vez, el pasado Septiembre. Llegó proveniente de Spelter para ver con sus propios ojos la tierra de su padre y abuelo. Los detalles más insignificantes, a veces, son las que suelen causar más sorpresa. Esa fue la impresión que tuvo durante sus caminatas por Piedras Blancas, Castrillón, de donde son originarios sus ancestros.

“Hay tantas cosas diferentes en Asturias”, dice Ron. “En Asturias, después de trabajar, la familia se va a la plaza principal del pueblo, los chicos juegan futbol, las señoras hablan de lo que tengan que hablar, los hombres hablan de quien sabe que. Estuve escuchando la plática de algunos de ellos y estaban hablando de que un día, del año pasado, algo sucedió; nunca averigüé que paso, pero tenían una discusión apasionada acerca de ello. Fui con mi primo a un café sobre la acera. Nos sentamos, bebimos café con leche y solo mirábamos a las personas pasar. Todas las mujeres traían puestos sus mejores vestidos, los hombres iban bien arreglados, al igual que los niños. Todos parecían disfrutar de la vida como tiene la vida que disfrutarse, hablando con personas que conoces, amigos que te topas en la calle, y si, también con las personas desconocidas, como yo. Luego te vas a casa en familia, cenas en familia, y pasas la tarde en familia”.

“Aquí en Virginia Occidental, llegas a casa después de trabajar y los niños no se encuentran en el hogar. Estarán en algún juego de pelota y tu esposa cocinando la merienda. Aquí no hay una plaza central del pueblo a la cual ir. Tampoco hay cafés sobre las aceras donde mirar a las personas pasar. Claro que hay bares a donde poder ir, pero no puedes llevar a tu esposa, como en Asturias. Aquí cenas, y luego te sientas a ver la tele toda la tarde hasta que es hora de dormir. En Estados Unidos, si no tienes coche, no puedes ir a ninguna parte. Estamos tan separados unos de otros que es imposible ir caminando”.

Lo que a Ron le pareció tan exótico en el extranjero, es lo que anhela en casa. A parte de la nostalgia, también encontró algunos símbolos de sus ancestros.

“Quería ver la tierra de mis abuelos, así como la de mi padre. Pero nunca encontré el hogar de la familia de mi padre. Nadie sabía donde estaba. Parece ser que lo mismo que pasa aquí pasa allá: mientras la gente mayor muere, esa parte de la historia se va con ellos. Creo que eso es muy triste”.

Ambas regiones, en Virginia Occidental y en Asturias, buscan maneras de preservar su pasado mientras miran para adelante. Nadie debería olvidar que el patrimonio industrial es parte de la cultura también. Nadie debería dejar que esa parte del pasado se olvide ni muera.

Este artículo fue originalmente publicado en inglés en la revista Goldenseal (Septiembre 2009).

Hello, just wanted to mention, I enjoyed this post. It was inspiring.

Keep on posting!

Thank you, Goede dag. You can also take a look at our facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/tracesofspainintheus

Thank you. You can also take a look at some pics and texts here: https://www.facebook.com/tracesofspainintheus

Do you know when and where the group photo was taken? I photoshopped this picture and it looks awesome. I would like to give it to you. Please tell me where to send it.

Dear Cathy,

I’ll check on the origins of the photo. I’d love to see the cleaned up version. My email is jf2@nyu.edu.

Best wishes,

Jim

Hi Cathy,

Would you please send me a cleaned up copy of the photo? One of the men in it may be my grandfather, but I would like a clearer view to be sure.

Bob Martinez

bobmartinez@robertmartinez.org