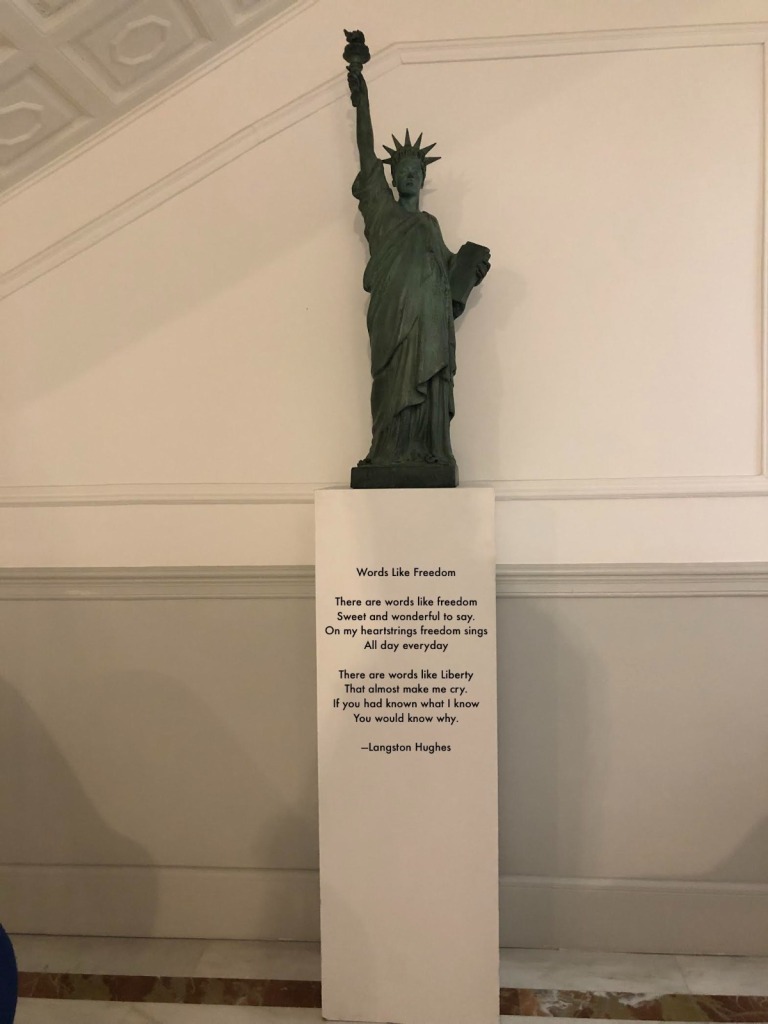

There are words like freedom/ Sweet and wonderful to say.

On my heartstrings freedom sings/ All day everyday.

There are words like Liberty/That almost make me cry.

If you had known what I know/ You would know why.

—Langston Hughes

“Liberty for All”, bronze statue by Fernando Sánchez Castillo, in the lobby of NYU Madrid, on loan from the artist and the Albarrán Bourdais Gallery, which occupies the ground floor of NYU Madrid’s academic site on Calle Barquillo.

Translations between languages can be treasonous. We’ve all probably heard that cliché: Traduttore, traditore; the translator is a traitor. But even within a single language, substituting a word with an apparently equivalent synonym can also sometimes approach the threshold of crimes and misdemeanors, with or without intent.

When, for example, my “deprivation” becomes their “austerity”, the thesaurus might more or less approve of the switch, but through this replacement my lived experience is being negated, and misappropriated; my misery is subsumed, without my consent, into a narrative of voluntary sacrifice made in pursuit of an alleged common good. My suffering becomes their virtue.

When her “nakedness” becomes the museum’s “nudity,” another act of non-consensual misappropriation and violence is being committed under the cloak of synonymity. Her self-possession becomes their show.

When their hard-fought and blood-splattered “freedom” is rendered in the clean and abstract “Liberty” found engraved on coins and statues, the particularity of the human struggle against the institution of slavery runs the risk of being subsumed under —and consumed by— the universalizing mantle of allegory.

The universal might pretend to contain and represent the local; but occasionally the general may actually be deployed to displace and efface the particular. Something strikingly akin to this occurs whenever certain people insist on rendering or altering “Black lives matter” as “All lives matter.” The second proposition pretends to magnanimously confirm and broaden the first proposition, when, in fact, when, in context, it more or less violently displaces and negates it.

In the mid-to-late 1860s, when the French abolitionist and admirer of the US, Edouard Laboulaye, and his sculptor friend Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi were imagining a monument that would celebrate the “liberté” of the United States: what exactly did they have on their minds? We can never know for sure, but there is plenty of evidence to suggest that the very recent abolition of slavery in the United States —1865– was one of the primary freedoms they hoped to celebrate in their monumental gift to the United States. But the ensuing history of the Statue conspired to almost completely erase from the popular US imaginary any link between the monument and the end of the institution of slavery. Its delayed construction —it wasn’t inaugurated until 1886: its eventual emplacement next to the Ellis Island Immigration Center in New York Harbor; the subsequent installation on the statue’s pedestal of a plaque inscribed with the text of Emma Lazarus’s famous sonnet celebrating immigration (1903): all of these factors most likely eclipsed or effaced the statue’s links to abolition.

The Spanish conceptual artist Fernando Sánchez Castillo, whose work constantly explores the friction between memory and monument, decided to recover, through research and imagination, creativity and technology, that lost link between Bartholdi’s colossus and the end of slavery. His project involves the creation of versions of Bartholdi’s female figure at many different scales, all with the same decidedly African facial features. Why isn’t Lady Liberty Black? What if she were Black? How might her blackness condition our interpretations of the statue? Our interpretations of US history? Sánchez Castillo and his gallery —Albarrán Bourdais, which, coincidentally, occupies the ground floor of NYU Madrid´s building— have generously agreed to place on loan in our lobby a bronze version of this remarkable work of art, so that we might daily ponder these and other important questions.

Students in the NYUMadrid class “Art Before/Beyond/Without Museums” (Spring 2023) are curating the installation of the sculpture —which we have come to call “The Statue of Freedom”— and are producing reflections on the artist, on the piece, and on the course, which they will leave here in a publication as a gift and a legacy to their successors. Those future students will come to Madrid, we hope, with a willingness to recognize and appreciate the differences between words and their apparent synonyms or cognates, between memory and monument, art and museum objects, raw materials and processed commodities, messy lived experience and packaged allegory, between the freedom that we dare to seize and exercise, and the Liberty that they pretend to grant us.

NYU Madrid students with the artist in the warehouse he shares with the artist Cristina Lucas in Usera, Madrid.